by Editors

You’ve discovered Bread and Circus, a group blog focused on culture. We’re no longer publishing new items, but we invite you to browse previous posts and articles.

You’ve discovered Bread and Circus, a group blog focused on culture. We’re no longer publishing new items, but we invite you to browse previous posts and articles.

Grey Gardens: What the Maysles’ Came-“lost” Can Teach Us

By Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard

In nurturing others we sometimes find ourselves. Yet, sometimes we lose ourselves as well.

What makes the difference? As “Little Edie” Beale points out in the Maysles Brothers’ cult-classic documentary, Grey Gardens (1975), life can be summed up “by three lines” [sic] from Robert Frost’s classic poem The Road not Taken (1916):

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both…

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

As straightforward as that sentiment may seem, Frost always maintained that the poem was a “very tricky one,” perhaps not to be read without irony. This is the sort of irony that the perceptive Little Edie perhaps saw in her own thwarted life, a life utterly devoted to her mother—the socialite-aunt of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis—“Big Edie.”

Thirty some-odd years later, their story continues to resonate with audiences. It was remade into an HBO dramatic special in July 2009 and the Tony-nominated musical version—which first hit the stage in 2006—recently made its way to Boston in May of 2009. Thus, it would seem that the tale of two resilient mondaines reduced to extreme reclusion, penury and squalor is at once bewitching and repulsive in its reality.

It was precisely the conflation of seemingly incompatible states of being with the Beales’ abundant charm that first gripped the Maysles Brothers. Originally the cinéma vérité-directing duo were approached by Lee Radziwill and her sister, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, about doing a documentary about their lives growing up in the Bouvier family. In researching the family, however, the Maysles came to the realization that their eccentric aunt and cousin living in a dilapidated, flea-infested East Hampton manse would make much better film subjects than Jackie and Lee.

The Beales’ allure? Perhaps it lies not so much in their patrician charm or their extreme living conditions, as in our own self-recognition in their dysfunctional, parent-child relationship. Add to that a nostalgia for the Seventies in all its campy glory, and—as Christine Ebersole noted in a February, 2007 interview on “Theater Talk”—the broader issue of societal disenfranchisement (whether of gays, women, or other underprivileged group) and you certainly have a hot topic for today.

Truly, the greatest attention paid toward the story does seem to come from the gay community. But why? Perhaps this phenomenon can be best-understood by comparing the Beales to another familiar gay-icon in popular culture, Bette Davis. In attempting to explain Davis’ popularity with gay audiences, for example, the journalist Jim Emerson wrote: “Was she just a camp figurehead because her brittle, melodramatic style of acting hadn’t aged well? Or was it that she was ‘Larger Than Life,’ a tough broad who had survived? Probably some of both.”[1]

Little Edie does seem to embody just this sort of fierce tenacity when she exhorts us with phrases like: “There’s nothing worse than a ‘staunch woman’….They don’t weaken, no matter what.” She follows the phrase with an “OK” hand sign, and a knowing look. Immediately, we, the audience, are with her. Adventurous types may also feel secret camaraderie with her in her flamboyant mode of dress: an affectation which evolved both out of her desire to cover her stress-induced Alopecia, combined with her child-like love of dressing-up and playing at starlet. The latter were inherited from her mother, once an amateur singer and performer. Both women enliven the long, empty hours spent at Grey Gardens by singing and dancing to the dated soundtracks of their youth.

Throughout the film we feel like voyeurs, intrigued and repulsed at the same time by the direct cinema techniques of the Maysles. Yet, the Maysles are successful in their endeavor to explore rather than exploit, because the film is not a simple act of gawking. Along with experiencing, perhaps, Thomas Hobbes’ comic sense of superiority, we also feel drawn to the humanity of the women. We are entranced by the same antipodes in their characters and circumstances that drew in the Maysles.

That said, in watching the original film, I have to say that at times the ladies’ bickering with one another seems to get the best of them. Yet, one coincidently also senses the inner-strength of these women, their devotion to each other, and their compulsion to provide daily nurturing for one another. As becomes increasingly apparent over the course of the film, however, this nurturing sometimes crosses a line that veers into unhealthy territory.

According to the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, “Codependency” is: “a psychological condition or a relationship in which a person is controlled or manipulated by another who is affected with a pathological condition (as an addiction to alcohol or heroin); or broadly: dependence on the needs of or control by another.” The dictionary also notes, interestingly, that the term “Codependency” was not coined until 1979. Thus, the Beales would not have heard of the condition at the time the documentary was filmed. Thus, they would not been availed of that lens through which to see their relationship.

You might say the predicament all started when Little Edie came back to East Hampton from Manhattan around the close of WWII to take care of her mother. At that time Big Edie was in poor health following an eye operation, and long separated from her husband. In her own words, Little Edie was “sick and tired of lying awake at night wondering what was happening to my mother.”

In her mother’s version of events, on the other hand, it was Little Edie who didn’t desire the glimmer of society’s spotlight in her debutante-youth. Big Edie says (in a rather philosophical way), “everyone thinks and feels differently as the years go by…”

And on and on it goes. The two women are in constant competition.

Upon Big Edie’s suggestion that—rather than her daughter’s patient—she was busy as care-taker of Little Edie for twenty-five years, Little Edie parries with: “The whole mark of aristocracy is responsibility…is that it?” To which Big Edie (somewhat humorously) screeches, “I’ll have to start drinking! I can’t take it. She’ll make a drunk out of her mother.” As each woman turns to the lens, the camera becomes their longed-for audience, we their boxing corner-men.

Twenty-five years into this codependency-melodrama, Little Edie still wonders, “When am I going to get out of here?” (She longed to be back in New York City above all.) “Any little rat hole, even on Tenth Avenue.” “I’ll just have to leave for New York City and lead my own life. I don’t see any other future.”

Though she longs for independence, Little Edie states that “I see myself as a little girl.” (Her mother’s little daughter.) And, congruently, her mother sees her as an “immature girl.” Little Edie perceives, however, that the filmmakers see her as a woman: precisely how she feels in New York City.

Indeed, according to her, living and loving in NY was her lifelong aspiration. According to Little Edie, she didn’t go into a nightclub act in her youth because: “[When] my father [Phelan Beale] was alive…That was it. Mr. Beale would have had me committed.” According to her, her father believed in running his children’s lives and wanted her to get an MA and become an assistant in his law office.

Then, there’s perhaps the most redolent scene in the film: when one of their dozens of feral cats goes to bathroom right behind Big Edie’s painted portrait. In a rebuke to Little Edie’s constant grousing, she quips, “I’m glad he is. I’m glad that somebody is doing something that he wanted to do.” It’s so unscripted, and so utterly fabulous.

A more subtle, yet remarkable development occurs when Little Edie’s stress-induced balding seems to abate. About halfway through the film, her hair begins to come back. Seemingly, she’s recuperating her selfhood and self-assuredness through the therapy of making the documentary. She even cleans the house, and redecorates, bit by bit. She makes little altars out of roses, childhood memorabilia, and souvenirs of some of her travels.

Similarly traipsing down her own memory lane, Big Edie listens to ancient records, and sings along—reminiscing about her thwarted singing career—whilst playing with her cats. Both matron and felines curl up on the bed together, Big Edie, singing You and the Night and the Music (1939): “Make the most of time, ere it has flown…”

In a fashion, the mother wants to perhaps keep her daughter from making the same mistakes—getting married, losing her independence and later suffering abandonment. Yet, she’s also seemingly jealous at her success in doing so.

The film is like an opera, the two voices intertwining, escalating and de-crescendoing as the Beales compete for center stage. In the end, they are more like star-crossed Gemini, twin mirrors of a forged reality from which they cannot escape.

In the end, Little Edie concludes that it is her mother’s house. And, that’s that.

She casually and quixotically remarks: “She’s a lot of fun, I hope she doesn’t die.” Of course, Big Edie eventually did pass away, a scant two years after the film was released, setting Little Edie free to pursue her aspirations of living in Manhattan and cabaret singing, fulfilling a lifetime’s worth of stardust dreams.

In closing, it bears mentioning that in the literature on the film, no one mentions the symbolism of Little Edie’s favorite fashion accessory—one that she wears throughout the film—an oblong brooch decorated with a wreath of roses and laurel sheaves. The two intertwining emblems are symbolic of “Love Victorious:” an apt metaphor for the spark of hope that Little Edie keeps kindled in her, the irresistible spark that draws us near, like moths to a flame.

_____

Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, Ph.D., is an editor of Bread and CircusMagazine and an Independent Scholar of Art History, specializing in Northern Renaissance and Baroque. Click here to send her email.

[1] Considine, Shaun. Bette and Joan: The Divine Feud. Backinprint.com. (2000), p 225. From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bette_Davis. Accessed: 5/24/09.

This is the last part in a 10-part series examining the loss and possible recapture of dignity in our public lives and political discourse. (Read the series from the beginning here.)

DIGNITY

By Stanley Baran

10. Achieving Dignity

In December, 2008 the Los Angeles Times acquired a leaked copy of a two-page internal White House memo intended for Cabinet members and other high-ranking Administration officials. Designed as a guide for discussing with the press and public President Bush’s eight years in office, it was titled “Speech Topper on the Bush Record.” It encouraged officials, among other things, to stress that Mr. Bush had throughout his two terms maintained “the honor and the dignity of his office.” Perhaps Mr. Obama’s successful invocation of dignity and his call to our better angels moved the White House to try to lay claim to some of Obama’s caché. Perhaps the Administration saw itself in the mirror and recognized an absence of dignity that, too late to be rectified, needed at least to be patched over. Perhaps dignity was just a word, a linguistic currency buying a basketful of extraordinary meanings, picked out of tradition, sounding presidential, and used to mark a transition. Whatever the reason for Mr. Bush’s desire to be remembered as a man of dignity, news of the memo led MSNBC’s Keith Olbermann to borrow from Senator Moynihan, telling his viewers that such a thing could come to pass only if Americans were willing to “define dignity down.”

But haven’t we been defining dignity down for some time? Rather than achieve the America embodied in our self-told stories, haven’t we allowed those cherished narratives to become detached from the realities they were intended to convey? Did we define our national dignity down to the point that our myth of exceptionalism morphed into what Glenn Greenwald called our “blinding American narcissism?” Upon the release of the December, 2008 bipartisan Senate Armed Services Committee report documenting the sanctioning torture by America’s highest level public officials, he wrote, “Just ponder the uproar if, in any other country, the political parties joined together and issued a report documenting that the country’s President and highest aides were directly responsible for war crimes and widespread detainee abuse and death. Compare the inevitable reaction to such an event if it happened in another country to what happens in the U.S.” Elsewhere he expanded on his theme of America’s narcissism, “The pressures and allegedly selfless motivations being cited on behalf of Bush officials who ordered torture and other crimes—even if accurate—aren’t unique to American leaders. They are extremely common. They don’t mitigate war crimes. They are what typically motivate war crimes, and they’re the reason such crimes are banned by international agreement in the first place—to deter leaders, through the force of law, from succumbing to those exact temptations. What determines whether a political leader is good or evil isn’t their nationality. It’s their conduct. And leaders who violate the laws of war and commit war crimes, by definition, aren’t good, even if they are American.”

But we are American, and we are proud of that. Yet when does our belief that we and our country are “wonderfully different from anything that has been,” in the words of philosopher Rorty, become undignified? Rorty, in a series of 1998 lectures on how leftist thought could help us “achieve our country,” addressed the issue of national pride, taking aim at a common pair of heuristics long employed to dismiss the suggestion that we, as nation, could do and be better—“America, love it or leave it” and its sibling, “My country, right or wrong.” He argued, “National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary condition for self-improvement. Too much national pride can produce bellicosity and imperialism, just as excessive self-respect can produce arrogance. But just as too little self-respect makes it difficult for a person to display moral courage, so insufficient national pride makes energetic and effective debate about national policy unlikely.”

Comedian Bill Maher was more succinct, demanding of his Real Time with Bill Maher studio and home television audiences, “Stop bragging about being the best country in the world and start acting like it.” On his Lincolnesque train trip to his Inauguration, Barack Obama was more expansive, reminding us that in our desire to be human rather than animal, we substituted reason for instinct. Speaking in Baltimore he said, “What is required is a new declaration of independence, not just in our nation, but in our own lives—from ideology and small thinking, prejudice and bigotry—an appeal not to our easy instincts but to our better angels.” Relying on ideology to reduce dissonance, depending on small thinking to arrive at the heuristics that free us from challenging our selfishness, retreating into prejudice and bigotry to make self-protecting attributions, those are indeed the easy instincts. No matter how hard it may be to define, no matter how infrequently we bump into it in our daily lives, we know that if dignity means anything at all, it means rising to the demands of our better angels, the good that resides in each of us and in those around us. Dignity had been leaving town well before the stolen Presidential election of 2000, but it is in the troubled years since that Americans seem to have reveled in its absence, substituting hollow myths and even emptier boasts for what was and is truly great about our country, our “nobility, courage, mercy, and almost all the other virtues which go to make up the ideal of Human Dignity.” If America means anything in the stories we tell to and of ourselves, it means that we are a nation of dignity. Few would deny that this is the greatest hope for our country; few can deny that we have failed to meet its demands. Will we do so now?

_________________

Stanley Baran is Professor of Communication at Bryant University. A Fulbright Scholar, he is the author of Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture and Mass Communication Theories: Foundations, Ferment, and Future. He writes frequently on the media, popular culture, and our understanding of ourselves and our world. He will happily provide citations for this series’ quotations and statistics. Simply e-mail him at sbaran@bryant.edu.

Text copyright 2009 Stanley Baran

____________

THE ARTS

Review: “Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist”

Herman Trunk and the Modernist Still Life is on view at Endicott College, Beverly, MA from October 15-December 18, 2009. For opening times and directions see the Endicott webpage.

The catalogue, Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009), is available at Lulu.com.

By Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard

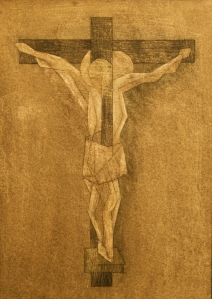

Crucifix (ca. 1930); Pencil with wax on paper; 10 x 14 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

With the advent of the modern world came an accompanying theory of secularization.[1] Enlightenment philosophers held that a developmental model of civilization demands that with modernization (read: rationalization) religion would necessarily decline.

Religion, of course, (in its broadest sense, including individual spirituality) has never left art or culture, and in a post-9/11 world I would suggest that even the most cynical critics would agree that life continues to be saturated with religious sentiment—spoken or unspoken.

In the visual arts, the period known as “Modernism” (the period from the turn of the last century until the 1960s) has been long associated with a firm commitment to individualism, iconoclasm and break with traditional institutions. This perspective became the mainstream means by which art critics and art historians came to measure successful art of the period.

In part, this perhaps explains why artists such as Herman Trunk, Jr. (1894-1963), a devout Roman Catholic who often imbued his paintings with overt symbolism, was exiled to the margins of American art history. This seemingly blind disregard for his work has recently impelled two Boston-area art historians, Cynthia Fowler and Dena Gilby, to reassess his religious and still-life works as masterful pieces in the Cubist and near-Surrealist styles. Fowler serendipitously discovered the artist in the process of researching her forthcoming book on hooked rugs designed by American modernists during the 20s and 30s.

The two scholars put together companion shows of Trunk’s work this Fall at their respective colleges: Fowler’s at Emmanuel in Boston (from 9/8-10/22) and Gilby’s at Endicott in Beverly (from 10/15-12/18). Fowler also organized and hosted a day-long symposium dedicated to the artist (“Religion and Modernism in American Art of the 1920s and 30s” on 10/3) and produced a handsome catalogue, Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009).

The catalogue contains essays by Fowler and Gilby, and also by Trunk’s nephew, Joseph (“Greg”) Smith. Smith grew up with the artist and his article sheds valuable light upon the man and anecdotes from his personal life, much of which was lived in Brooklyn, NY. Smith’s family photos and stories help to flesh out the biographical and iconographic picture painted by Fowler in her introductory and main essays. Fowler’s essays and show loosely cover Trunk’s figurative and landscape works, while Gilby’s are focused upon his still-lifes and flower pieces.

The artist that emerges from the well-illustrated catalogue is a complex and—at times—contradictory figure. Contradictory, perhaps, because of our own (aforementioned) inherited bias about what constitutes a Modern painter in the abstract style. We do not usually imagine, for example, a dedicated family man who sentimentally paints his wife’s Valentine’s chocolates, or the interlocking “Sacred Hearts” of Jesus and Mary in order to grieve the loss of his mother in visual terms.[2]

Sacred Hearts (1930); Watercolor and gouache on board; 20 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

It is Trunk’s return, perhaps, to tried-and-true symbols of traditional Christianity that sets him apart from his contemporaries such as Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe: artists with whom he was shown side by side at the Biennials of the Whitney Museum of American Art and Venice in his heyday.

Viewed in-person, the works are astounding for their rich color-sensibility and harmonies of geometry. Many are in either watercolor or gouache media, with only a couple in oil. According to Gilby,[3] during the Depression and war years the artist worked full-time in his family’s print shop, and often painted after-hours. Thus, this choice may have been due to monetary constraints, reasons of convenience, or both.

Luckies (1925); Oil on board; 10 x 8 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

Indeed, the watercolors and gouache seem to be more adroitly handled than the oils, but the oil medium seems to have allowed the artist to work up thick impasto in order to gain sculptural effect and depth that challenge the two-dimensionality of the surface. The same insistence on delving into space is found in his beaverboard piece, “Artist’s Palette” (n.d.; Oil on board), where the artist incises geometric shapes into the surface, outlining his color passages and allowing the wood grain to show through. This treatment is reminiscent of Picasso and Braque’s experiments with Synthetic Cubism and work-a-day materials, and may have been learned during Trunk’s time at the Art Students League.

Interestingly, Gilby has also included a long vitrine in the Endicott show housing one of Trunk’s notebooks as well as some personal correspondence and family photographs. This archival material is an advantageous corollary to the still-lifes and landscapes. Further testament to continued strong family-ties among the Trunks, it was also brought to my attention that the frames for many of the works were hand-fashioned for the exhibitions by the artist’s nephew, including the attractive multi-layered bronze-colored frame surrounding “Black-Eyed Susan.”[4]

Far and away the greatest contribution made by the catalogue essays is that they frame Trunk’s work not according to his experimental style—as was done in a Hirschl and Adler Galleries retrospective in 1989[5]—but, rather through the lens of his Catholic faith. This faith is expressed in his use of traditional symbolism as well as his imagery redolent of nature as God’s creation.

The authors take great pains to explain how devout Trunk, his wife Irene, and indeed the whole Trunk family were. There are images of the local parish, stories about faithful trips to morning mass, and accumulated evidence of attention paid to traditional Biblical narrative, Catholic iconography as well as the imbuing of everyday objects with personal, devotional significance.

True, there are passages in the writing where one might wish for more in-depth analysis of the iconography of the works: for example, greater discussion of the floral and fruit symbols like roses and oranges most often associated with Mary, mother of Christ; or the use of jewel tones and thick outlines reminiscent of stained glass; or the use of metallic paint which calls to mind a long history of gilt panel altarpieces. However, the description of “Trees” (Cat. 6, c. 1930-35, watercolor and pencil on paper) as cathedral-like is enticing, as is the likening of the oft-mentioned tenets of mysticism in the vein of Kandinsky to those of “conventional faith.”[6] Overall the essays serve as an even-handed, valuable introduction to the artist and his unique milieu.

The catalogue and exhibition are highly recommended to those interested in Modern art, religious iconography, or a reconsideration of how the two might be considered more fruitfully in tandem.

________________

Addendum:

Since the original publication of this article, Dr. Gilby has brought to my attention that the title of the Endicott Show differs from the one I first listed here, the one published on the catalogue overleaf, in fact. I have fixed this above, correcting the title to read “Herman Trunk and the Modernist Still Life,” instead of “Modernist Specters in the Still Life Paintings of Herman Trunk, Jr.” as previously stated.

Furthermore, (in personal correspondence) Dr. Gilby takes slight issue with my assertions that her catalogue essay and the Endicott show “are specifically focused on Trunk’s Catholicism.” Though I may not have expressed with enough clarity Trunk’s many-layered connections to the worlds of Modern Art and the New York scene, I would maintain that the thread of Catholicism is readily interwoven into Gilby’s show and essay.

Agreeing whole-heartedly with Dr. Gilby, I would simply state that Trunk is a versatile, talented artist whose art is well-worth experiencing on any of a number of levels.

-Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, November 21, 2009

[2] Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009), pp. 28-29.

[3] In a personal conversation on 11/6/2009.

[4] Again, personal conversation with Dena Gilby on 11/6/2009.

[5] See the exhibition catalogue, Herman Trunk (New York: Hirschl and Adler Galleries, 1989.)

[6] Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist, pp. 23, 25.

_____

Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, Ph.D., is an editor of Bread and Circus Magazine and an Independent Scholar of Art History, specializing in Northern Renaissance and Baroque. Click here to send her email.

________________

BOOKS + IDEAS

ON CONSERVATIVE INTELLECTUALS AND RICHARD NIXON:

AN INTERVIEW WITH HISTORIAN SARAH K. MERGEL

By G. Arnold

Richard M. Nixon was one of the most influential and puzzling figures in American politics of the twentieth century. His legacy looms so large that it is often easy to gloss over his complexities. A deeply intelligent and astute politician, he was nonetheless a polarizing figure.

Sarah K. Mergel, a professor at Dalton State College in Georgia, specializes in American political and intellectual history. She has studied Nixon and the Conservative Movement in detail. Now she has a new book, Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon (Palgrave Publishers, 2010), which reconsiders the complicated relationship between Nixon and other conservative leaders in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As her book reveals, it’s a fascinating story.

Having known Sarah K. Mergel from her previous essays in Bread and Circus, we thought it would be interesting to ask if she could tell us a bit more about her book and the ideas in it. Here is what she had to say.

______

Bread and Circus: Your new book touches on important aspects of American political history. Can you tell us what it’s about and why you decided to write it?

Sarah K. Mergel: Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon explores the relationship between postwar conservatives and the president from 1968 to 1974. The more I read about the growth of the conservative movement after World War II, the more I realized that the conservatives would rather forget their experience with Richard Nixon. They failed to see how his presidency helped refocus their fight against liberalism and communism. Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon uses the Nixon years as a window into the right’s effort to turn their ideas into a program more voters could relate to. It combines an assessment of Nixon’s presidency through the eyes of conservative intellectuals with an attempt to understand what the right gained from its experience with one of the most interesting American presidents in the twentieth century.

B&C: Richard Nixon was a man of great intelligence and political skill. His long political career had many highs and lows. As someone who has spent considerable time studying Nixon and his influence, what do you think is the most important thing that we should understand about Nixon, the politician?

Sarah K. Mergel: Ever since Watergate traumatized the nation, people have been trying to understand Richard Nixon. Based on my own study of Nixon, I think the answer is pretty simple. Everything he did during his long public life, especially after he became president, looked to his historical legacy. At heart Nixon was a practical politician; he made choices throughout his career that he thought would enhance how people would view his contribution to American life. Nixon never expected to be mired in a scandal that would do so much damage to his reputation at the time or in the future.

B&C: Looking back at his long and remarkable career, what do you think was Nixon’s most important success?

Sarah K. Mergel: I cannot point to one policy or action that Richard Nixon took that stands out as his most important success. However given the length of his political career from the late 1940s until his death in the 1990s, probably his most important success was that he was a survivor. Nixon managed to rebuild his career more times than any politician that comes to my mind.

B&C: Although people often talk about conservatism and liberalism, it seems there is not always agreement on what labels mean. How should we understand “conservatism” in the context of the era you discuss in your book?

Sarah K. Mergel: Conservatives essentially called for three things before and during the Nixon era. First, they wanted a strong national defense to prevent the spread of communism. Second, they promoted what they considered a greater respect for tradition and order. Finally, they wanted a less influential federal government in terms of social and economic policy. Simply put, they did not share the liberal’s belief that the government could or should solve all of society’s problems. They did believe that the government should protect American citizens from totalitarian threats.

B&C: Your book talks about Nixon’s relationship with the changing conservative movement. What kind of relationship was that?

Sarah K. Mergel: Richard Nixon knew he needed the support of the conservative movement as well as what he would later call the silent majority to win in 1968. In large part, Nixon lost the 1960 election to John F. Kennedy because conservatives within the Republican Party would not vote for him. The right supported him in 1968 because they thought he supported conservative policy solutions. Nevertheless, his relationship with the movement remained tenuous well into his presidency. In some instances he tried to win its support by making connections with conservatives like William F. Buckley, Jr. and Russell Kirk. But as much as conservative intellectuals wanted to believe Richard Nixon leaned to the right they always doubted his loyalty to their cause. To some extent, their doubt was well placed since he went against almost every conservative principle he pledged to uphold in 1968. He courted the conservatives when he needed them and ignored them much of the rest of the time. Richard Nixon used the conservative movement; however in the end the conservatives benefitted more from their strained relationship than did the president.

B&C: What was the biggest effect that Nixon had on the conservative movement?

Sarah K. Mergel: The conservatives widely supported Richard Nixon in 1968 and so they expected that once he took office they would have a good relationship with his administration and his policies would move the nation to the right. Since neither of these hopes came true, conservatives began to redefine their movement by distancing themselves from Richard Nixon and his policies. Essentially the biggest effect Nixon had on the conservative movement was not anything he did, but what he did not do. His failure to live up to their expectations prompted leading conservatives to no longer accept the closest thing to a conservative who could win an election (as they did in 1968). The right learned to stay true to their ideology when choosing a candidate. Their dedication paid off—in their opinion—when Ronald Reagan won the presidency in 1980.

B&C: Among leading conservatives, who do you think were some of those most affected by Nixon and his presidency? How so?

Sarah K. Mergel: Conservative politicians — like Barry Goldwater and Strom Thurmond — seemed less affected by Richard Nixon’s presidency than conservative intellectuals –like William F. Buckley, Jr., James Burnham, and William Rusher. The bitter disappointment felt by those intellectuals working with National Review and other conservative publications led them to rethink in some ways how they approached politics, especially future presidential races. More than anything else, conservative intellectuals and strategists realized they would have to work harder to make conservatism an acceptable political choice as opposed to something seen as a reactionary political choice. They also needed to branch out to groups not previously identified as political conservatives like disaffected liberals and evangelical Christians.

B&C: Looking at it the other way, who, if anybody, among the leading conservatives, influenced Nixon the most?

Sarah K. Mergel: Richard Nixon always seemed to want the respect of the intellectual community—both right and left—and yet he seemed to do everything possible to push them away. On the conservative side, when he took office he had a decent relationship with William F. Buckley, Jr. and Milton Friedman. However, to say that these men or any other conservative intellectual influenced Richard Nixon long term would be a stretch. At various points in his career he embraced right-leaning ideas but in the end Nixon was always his own greatest influence.

B&C: When, in your book, you talk about the Right’s effort to turn ideology into successful politics, what do you mean?

Sarah K. Mergel: The Right, in the years after World War II, began to outline their challenge to liberalism and communism and it seemed to leading conservatives no one was listening. Partly because of the social changes social changes in the 1960s and partly because of Richard Nixon’s presidency the right learned to how to promote their ideas to a wider public. Not only did they learn to sell those ideas to the people, but they learned how to see their candidates elected to public office. Conservative Richard Weaver once talked about ideas having consequences; what the Right learned from their experience with Richard Nixon was to how to show people those consequences.

B&C: Finally, what is the most important thing that you think people should take away after reading your book?

Sarah K. Mergel: National Review publisher William Rusher called the conservative decision to support Richard Nixon the “blunder of 1968.” The idea that Nixon’s presidency somehow setback the conservative movement seems wrong. When wage and price controls failed to curb inflation in the 1970s and détente failed to bring world peace, conservatives (who had been questioning those policies from the beginning) benefitted. The most important thing to take away from Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon seems to me that sometimes in politics your biggest blunder can turn into your greatest advantage.

__________

Sarah K. Mergel’s Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon will be released by Palgrave Publishers in early 2010.

G. Arnold is an editor of Bread and Circus Magazine and the author of several books, including Conspiracy Theory in Film, Television, and Politics and The Afterlife of America’s War in Vietnam.

Image (above): National Archives photograph (unrestricted) of a Nixon campaign trip in 1972.

_____________

Image from Teensy Weensy Book

4.25″x4.25″

Kristine Williams, 2009

“This is a book project I’m working on. Almost every piece has a cutout, or what I’m calling cliffhangers in this series.” –K. Williams

For more, visit the artist’s blog here.

© 2009 Kristine Williams. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission.

_______________________

This is the ninth in a 10-part series examining the loss and possible recapture of dignity in our public lives and political discourse. (Read the series from the beginning here.)

DIGNITY

By Stanley Baran

9. The Stories We Tell (About) Ourselves

In April, 2007, without explicit reference to any well established psychological theories, novelist and social critic E.L. Doctorow addressed the issue of Americans’ penchant for protecting themselves from the onus of fully engaging their world and others in it. Speaking to a joint meeting of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society on the theme of “The Public Good: Knowledge as the Foundation for a Democratic Society,” he entitled his keynote speech, “The White Whale.” Rather than make rumor the starting point for his analysis of how we reshape reality to render it more manageable, as Allport and Postman had done six decades earlier, Doctorow chose literature. “Melville in Moby-Dick,” he said, “speaks of reality outracing apprehension. Apprehension in the sense not of fear or disquiet but of understanding. . . reality is too much for us to take in, as, for example, the white whale is too much for the Pequod and its captain. It may be that our new century is an awesomely complex white whale. . .What is more natural than to rely on the saving powers of simplism? Perhaps with our dismal public conduct, so shot through with piety, we are actually engaged in a genetic engineering venture that will make a slower, dumber, more sluggish whale, one that can be harpooned and flensed, tried and boiled to light our candles. A kind of water wonderworld whale made of racism, nativism, cultural illiteracy, fundamentalist fantasy and the righteous priorities of wealth.”

What is more natural, in other words, than relying on heuristics? What is more natural than selectively perceiving the world and others occupying it in ways that reduce discomfort, even if in doing so we ourselves are reduced? What is more natural than attributing our successes to our fundamental goodness and the shortcomings of others to their fundamental failings? What is more natural than refusing to dignify any reality that requires us to consider the world and others occupying it as anything more than an It threatening our I?

They hate us for our freedoms. The new Hitler. Socialized medicine. Support the troops. Welfare queens. These colors don’t run. East Coast elites. The invisible hand of the market. The kind of guy I’d like to have a beer with. The ticking bomb and the mushroom cloud. All are heuristics designed to short-circuit elaborated analysis and to attribute any failing, any unpleasantness, any selfishness to things and events outside our control; all are part and parcel of a people unwilling to do the critical thinking that is the hallmark of both dignity and its political manifestation, democracy. As Allport and Postman’s post-World War II research suggests, this isn’t a new phenomenon, but it seems to have fully matured in the Bush years. Recall Ron Suskind’s 2004 New York Times Magazine piece entitled “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush.” Arguably, its most quoted passage is this exchange with an unnamed White House staffer. “The aide,” wrote the Pulitzer Prize winner, “said that guys like me were ‘in what we call the reality-based community,’ which he defined as people who ‘believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.’ … ‘That’s not the way the world really works anymore.’”

Suskind’s unnamed aide continued to explain that as the world’s lone superpower, “we create our own reality.” Of course, all nations and cultures create their own realities. They exist in the stories a people tell of themselves. As philosopher Richard Rorty explains, “Stories about what a nation has been and should try to be are not attempts at accurate representation, but rather attempts to forge a moral identity.” They are narratives designed to express a people’s highest hopes, greatest goodness, deepest honor, and commitment to dignity. The stories a people tell to themselves are the stories they tell about themselves. When we think of England’s mythology, we see Knights of the Round Table and King Richard, not its colonization and enslavement of the people of India. We remember the French Resistance in World War II, not the collaborating Vichy government, turning helpless Jews over to their Nazi killers. We teach our children the wonderful story of the Founders and their struggle against the tyrant King George as they gave birth to the world’s greatest democracy. But when we get to the stories about our Civil War that emancipated the slaves living here in the freest country in the world, we omit the fact that slavery had been outlawed in England 30 years before, during the reign of the tyrant’s son, William.

What happens when a country’s defining stories are used not to embody its honor and dignity, but to justify a “reality” that conflicts with the reality those stories purport to hold? Vietnam veteran and international relations expert, retired Colonel Andrew Bacevich, calls our national mythology “stories created to paper over incongruities and contradictions that pervade the American way of life,” and James Baldwin, in The Fire Next Time, offered this example of how “white Americans” during the Civil Rights era papered over the incongruities and contradictions inherent in their treatment of their fellow citizens of different skin color. They told themselves that “their ancestors were all freedom-loving heroes, that they were born in the greatest country the world has ever seen, or that Americans are invincible in battle and wise in peace, that Americans have always dealt honorably with Mexicans and Indians and all other neighbors or inferiors, that American men are the world’s most direct and virile, that American women are pure.” Even today we celebrate “The Greatest Generation” for its World War II defeat of global fascism while failing to question the greatness of a generation that racially segregated the armed forces that secured that victory, while at home German POWs could enter Southern diners that were off limits to American Blacks, and more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry, 60% American citizens, were herded into internment camps.

In Myths America Lives By, Pepperdine University religion professor Richard T. Hughes argues the existence of “five foundational myths” that produce a dominant narrative of American exceptionalism: America is the chosen nation, the Christian nation, nature’s nation, the millennial nation, and the innocent nation. Speaking to a 2004 conference, Hughes explained how this narrative protected Americans’ cognitive consistency after the 9/11 attacks: “Americans have by and large refused to face the question of ‘why they hate us’ head-on. Instead. . .they have taken refuge in the venerable myth of American innocence. To claim our enemies hate us because they hate liberty is simple a way of asserting American innocence without coming to grips with the awful truth that our enemies hate us for many clear and definable reasons.” No need to debate why many of our most trusted allies did not support the invasion and destruction of an entire Muslim society; we are chosen, we are righteously Christian, this is our century. No need to dredge up our decades of dealing with Saddam Hussein, the arming and training of the Taliban, the overthrow of disfavored democratically elected political leaders, and our unwanted presence in the Middle East; we are innocent.

As accounts of the killing in Iraq, images of torture at Abu Ghraib, and tales of institutional incompetence and personal viciousness in Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath filled the world’s newspapers and television screens, Dermot Purgavie, veteran U. S. correspondent for London’s Daily Mirror, wrote of the nation he covered, “Americans are the planet’s biggest flag wavers. They are reared on the conceit that theirs is the world’s best and most enviable country, born only the day before yesterday but a model society with freedom, opportunity and prosperity not found, they think, in older cultures.”

Indeed, we do think ourselves exceptional, but it is impossible to reconcile exceptionalism with dignity. If exceptional means special or superior, such self-aggrandizement is itself undignified. If exceptional means that we are the exception (the rules we apply to others do not apply to us), we are operating not in a dignified I-Thou manner, but in a state of undignified I-It.

Read Part 10: Achieving Dignity (click here)

_________________

Stanley Baran is Professor of Communication at Bryant University. A Fulbright Scholar, he is the author of Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture and Mass Communication Theories: Foundations, Ferment, and Future. He writes frequently on the media, popular culture, and our understanding of ourselves and our world. He will happily provide citations for this series’ quotations and statistics. Simply e-mail him at sbaran@bryant.edu.

Text copyright 2009 Stanley Baran

_________________________________

COMMUNITY

Stone Soup Stewardship: A Thanksgiving Tale

By Kimberlee Cloutier-Blazzard

.

Many of you are no doubt familiar with the old story, “Stone Soup.” In the tale, a group of reluctant villagers eventually create a soup together, bit by bit, in order to help feed some hungry travelers. In doing so, they learn to open themselves up to the strangers in their midst through the selfless act of sharing.

It is an old chestnut that one might look at the world as a village. At Thanksgiving time, especially, it is important to reflect on all the things we have in our country—even when we’ve recently learned to focus on our shortfalls—and turn our minds to the hungry and needy here and abroad. In doing so, we might see ourselves as a potential donor of one of the Ingredients needed for some much-needed stone soup: “Care for others and the world.”

This ingredient describes the way that we might choose to participate in community and world outreach—in what many churches refer to as their “Missions” component. Missions includes things like a Walkathon for a children’s summer camp, a food pantry, soup kitchen, local or world disaster relief organizations (providing such things as school supplies, hand-made quilts and health kits), Fair Trade Coffee, projects in Africa, a college campus Food-Not-Bombs Freeganism initiative, and so on. Of course this idea is not limited to churches, but I do believe that there is an important reason for working together on these initiatives.

Here’s a thought. While we can imagine doing this type of outreach ourselves, singularly, when we do this together as a group we’re more powerful—both spiritually and materially.

Here’s a fact. Sometimes when we act alone to help others, we consciously or subconsciously get into a “siege mentality”—believing that we’re living inside a tiny fortress with a forbidding world outside.

In that instance, though we give to others, to a degree we remain worried about our own personal time, resources and personal finances. We worry that we are not setting aside enough for our own future need. Thus, we continue storing up unused goods and funds and girding ourselves against strangers. We bury our ‘talents,’ in a manner of speaking.

When we do this in some ways we are like the Stone Soup villagers whose first reaction to the itinerant men was to shut their doors, ears and hearts to the poor and needy.

However, when we realize that we are not just acting for today, but that—together as a world—we are busy building a better place here on earth, then we become aware that those who we imagined to exist on the other side of our door are actually on the inside, members of our same loving community.

To realize this is to understand the poignant wisdom of St. Francis of Assisi, spoken so many years ago: It is in giving that we receive.

For, indeed, when we share our time and resources—our ‘talents’—we are really opening a connection with others in our world community, to our own brothers and sisters.

I like to think of it in this very tangible way:

When I give food to my local Open Door Pantry, for example, I may be taking food out of my cupboard, leaving a temporary space in there—but even so—I’m never afraid that my own family will go hungry. WHY?

First, because I know that I am doing the right thing by feeding those who are hungry NOW. That food is worth so much more in their empty bellies than it is in my storehouse. That’s a very comforting feeling.

But, moreover, I know very well that someday I might find myself in their shoes. And, if I ever did get to the point where I had a bare cupboard and hungered, I have faith that the Open Door would be there for me—ready to return the favor—stocked by folks just like me who gave because they believe in spreading the wealth here on earth.

The example can be multiplied a hundredfold: think about that winter coat you don’t wear anymore, or the toys your kids don’t play with, or even those 10 extra inches of hair! (My eldest daughter and I gleefully shared the latter “kindest cut” side-by-side in a salon last year.)

In giving, we invest in the others in our community who are currently on the down cycle of fate’s ever-turning wheel.

In giving, we remember that even when things are going well in our home—when we’re on the ascent in the world—there are others who are hungering and thirsting—literally or metaphorically. Such as the people of Wunlang, South Sudan for whom I’ve worked and written about building a new water well.

In closing, this is why we should work together to build a better world, stone by stone, here and now, with hand, heart and all the resources given us. For, we are our brothers’ keepers and when we do justice to the least of us, truly we cause great joy and healing.

_____

Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, Ph.D., is an editor of Bread and Circus Magazine and an Independent Scholar of Art History, Specializing in Northern Renaissance and Baroque. Click here to send her email.

This is the eighth of a 10-part series examining the loss and possible recapture of dignity in our public lives and political discourse. (Read the series from the beginning here.)

DIGNITY

By Stanley Baran

8. Leaving the Reality-Based Community

Comedian George Carlin famously wondered why we think that anyone who drives slower than we do is an idiot and anyone who drives faster than we do is a maniac. Of course, the answer resides in people’s need to reduce dissonance, avoid elaboration, and find comfort in heuristics. But what if this isn’t enough? What if for some reason we need more evidence to protect ourselves from the realities that surround us? Psychologists offer attribution theory to explain. In its simplest terms, attribution theory posits that humans minimize dissonance and avoid elaboration through attribution error.

Social scientists such as Fritz Heider in the 50s and Harold Kelley in the 60s argued that people, as they encounter various situations and their roles in them, act as “scientists,” trying to figure out the “why” of the behaviors they observe, both their own and others. An internal attribution locates within the person the “why” of an observed behavior; an external attribution places it with the situation. Although all people can and do engage in internal and external attributions, we have a natural tendency to apply external attributions to our own behaviors and internal attributions to the behaviors of others.

Revisit Mr. Carlin’s driving conundrum. You’re in the fast lane, going 5 miles-an-hour over the speed limit. Another driver comes up on your tail and flashes the car’s high-beams. You make an internal attribution for her, “What a maniac! Why do people have to drive so fast?” and an external attribution for yourself, “Besides, I have to be in this lane; there are too many big trucks in the right hand lanes.” Now put yourself in the second car, flashing your high-beams. You make an external attribution for yourself, “I’m late for work; I just gotta get there on time or I’ll be in trouble” and an internal one for the driver in front of you, “What an idiot! Why do people always drive so slow?”

Dignity demands that we hold ourselves to the same standards that we do others, that we take responsibility for our actions just as we assign responsibility to those who act around us. Because we humans “invented” dignity, choosing to monkey with concepts to rise above the instinctive need for mere self-preservation, dignity demands that we see the world through an I-Thou rather than an I-It lens. But for the last decade or so Americans have been encouraged to and rewarded for locating our achievements internally and our failures externally. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, for example, we, led by our political leaders, went external. Despite an August 6 memo delivered to the Oval Office entitled “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US”, Bush officials attributed their failure to anticipate the attacks to Bill Clinton; he hadn’t done enough about al-Qaeda when he was President. The failure to comprehend the seriousness of the threat could not possibly be attributed to their misreading of the memo, claimed Condoleezza Rice. The then-National Security Adviser told the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States that it was the document’s fault for being merely an “historical memo. . .it was not based on new threat information. . .No one could have imagined them taking a plane. . .using planes as a missile.’” Thusly protected, no official resigned (in fact, several were promoted or given medals). Thusly mollified, the pitchforks remained sheathed; Americans made no demand for resignations. Even after subsequent evidence demonstrated that the memo did indeed offer new al- Qaeda threat information and specifically envisioned just such an attack, Americans returned these same people to office, Mr. Bush becoming the first president to win an absolute majority of the popular vote since his father, George H.W., in 1988.

In the wake of the November 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, India, in which 170 people were killed, in contrast, several highly placed government officials, making internal attributions, did resign. National Security Advisor M. K. Narayanan and Home Minister Shivraj Patil admitted that warnings of the assault had been raised but they had not adequately responded to them. Patil wrote to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh “owning moral responsibility” for the failure. The Chief Minister for security matters for Maharashtra (the state where Mumbai is located) also stepped down. Vilasrao Deshmukh told an interviewer, “I have accepted moral responsibility for Mumbai terror attacks. In a democracy one has to honour people’s anguish and anger.”

Attribution error is a powerful tool of cognitive self-preservation. Five years after the 9/11 attacks, President Bush was granting his “farewell tour exit interviews” in anticipation of leaving office. On December 1, 2008 on ABC’s World News Tonight, anchor Charlie Gibson asked him if going to war in Iraq had been a mistake. Unlike India’s politicians, the Decider decided to attribute blame elsewhere, “A lot of people put their reputations on the line and said the weapons of mass destruction is (sic) a reason to remove Saddam Hussein. It wasn’t just people in my administration. A lot of members in Congress, prior to my arrival in Washington, D.C., during the debate on Iraq, a lot of leaders of nations around the world were all looking at the same intelligence. . .I wish the intelligence had been different, I guess.” As for the financial meltdown that cost millions of Americans their jobs, homes and savings in the last year of his presidency? He attributed that to his father, the first President Bush, “You know, I was the president during this period of time, but when the history of this period is being written, people will realize a lot of the decisions that were made on Wall Street took place over a decade or so before I arrived in president [sic].”

Read Part 9: The Stories We Tell (About) Ourselves (click here)

_________________

Stanley Baran is Professor of Communication at Bryant University. A Fulbright Scholar, he is the author of Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture and Mass Communication Theories: Foundations, Ferment, and Future. He writes frequently on the media, popular culture, and our understanding of ourselves and our world. He will happily provide citations for this series’ quotations and statistics. Simply e-mail him at sbaran@bryant.edu.

Text copyright 2009 Stanley Baran

_________________________________

NEW VOICES / JOURNEYS

Freedom Paintings

By Jessica Miles

While studying abroad this past June in Prague, Czech Republic, I traveled outside the city to gain a better understanding of the effects of Nazism on the country. I arrived in Terezín on a hazy Saturday afternoon and toured the Small Fortress of the Terezín Ghetto where thousands of prisoners were held against their will during the Holocaust.

“It mustn’t be forgotten,” she said.

This is why Mrs. Helga Weissová-Hošková visited that day; this is why she spoke. Mrs. Weissová-Hošková had come to share her story as a Holocaust survivor from Prague who was sent to the Terezín Ghetto on December 17, 1941. She was twelve when she arrived at Terezín.

“It mustn’t be forgotten,” she boldly stated.

She toddled into the room that day in a taupe pant suit and a clunky gold necklace holding a purse that was half her size on her forearm. She was no more than five feet tall with a slight arch in her back, salt and pepper hair, and crystal blue eyes. She gently placed her bag down on the chair and paused.

“I am here…to tell you…my story,” she said in broken English.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s nightmare began in Prague in 1941, when the Nazi regime expanded to the Eastern Block. She did not know her fate that day when her family was forced into a crowded truck and blindly relocated one hour away to Terezín, a small town in northwest Czechoslovakia. The Nazis had transformed Terezín into a labor camp where Czech Jews would work before being transferred to a concentration camp.

In December 1941, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her parents arrived at the Small Fortress of Terezín. Arbeit Macht Frei, read the message over the entranceway. Work Brings Freedom. The brick fortification surrounded by sprawling green hills was secluded and bare. Barbed wire lined the fortress walls, which were adorned with barred windows and doors.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s home was in the barracks of the Small Fortress isolated from the outside world. She was housed with several other Czech Jews. Yet, even in the dismal conditions, together they created normality however they could.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s home was in the barracks of the Small Fortress isolated from the outside world. She was housed with several other Czech Jews. Yet, even in the dismal conditions, together they created normality however they could.

“We kept our traditions. We were always together,” Mrs. Weissová-Hošková said as she recalled lighting the Chanukkah menorah in a dark loft within the fortress. She remembered gathering around the menorah with the other children, their eyes brighter than the burning flames.

However, the desolation overshadowed the mere moments of contentment. The smell of rotting bodies, the threat of typhoid, and the lasting despair lingered around every corner of the ghetto, but she never lost hope.

By night Mrs. Weissová-Hošková was crammed into the rickety wooden bunks overcrowded with emaciated figures yearning for sustenance as bugs crept across their frail bodies. By day she was one of thousands of Jews identified by the yellow Star of David on her sleeve, which she still carries with her.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková considered herself quite lucky, as she was never separated from her mother during the selection process. Her father was not so fortunate.

“We were told we were going to another ghetto. My father went ahead of us. I did not know I would not see him again,” she said. “We never found my father’s name on the lists [of prisoners registered at Auschwitz]. He was probably gassed before arriving at Auschwitz.”

Days later in October of 1944, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her mother were loaded into crowded trucks and once again blindly transferred from Terezín to Auschwitz. Sixteen days later, along with thousands of other Czech prisoners, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her mother were liberated by the Soviet army in 1945.

* * *

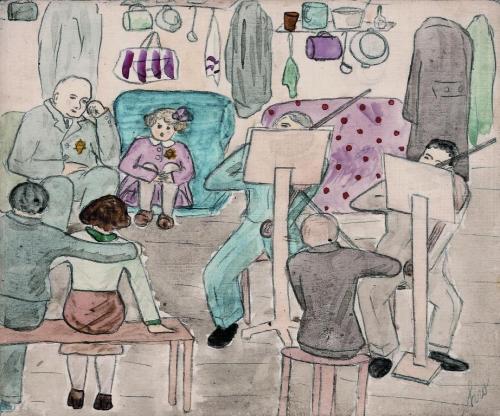

Aside from her words Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s story is also told through her artwork. With her paints and brushes, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková painted the truth behind the walls of the Small Fortress and was eager to share her work that day.

Violinists in the barracks. This painting of three prisoners providing entertainment in the barracks of the Small Fortress represents an escape from Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s surroundings. It is a symbol of unity; a man wraps his arm around a woman, while a young girl holds her knees to her chest as she listens to the violinists draw their bows along the strings of the violins.

_____

Terezín’s children. This painting symbolizes the children of Terezín who banded together and celebrated the traditions closest to their hearts. Lighting the Chanukkah menorah was one such tradition that took place within the walls of the barracks.

_____

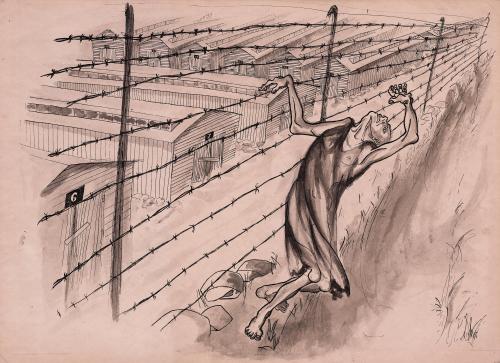

Vanished hope. A man falls against the jagged wall of barbed wire surrounding the Small Fortress. “This man had no more hope. He did not want to live anymore,” said Mrs. Weissová-Hošková. His gaunt figure falls to the ground, his hands still grasping the piercing barrier.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s drawings were later recovered following the termination of the Nazi regime and represent a cultural commemoration to the battle millions of prisoners fought for survival. Today, she is recognized internationally for her artwork and as an outspoken survivor of the Holocaust. Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s pieces have been featured in several exhibitions, including A Child Artist in Terezín: Witness to the Holocaust. She has also been spotlighted in various publications for sharing her voice and her art with those who believe in her message, for those who believe it mustn’t be forgotten.

_________

Jessica Miles is a Bread and Circus Magazine contributing writer.

Text and photographs © 2009 Jessica Miles.

Paintings © 2009 Helga Weissová-Hošková. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of the Artist.

Thanks to Milan Polák of CIEE, Council on International Educational Exchange, for assistance in the preparation of this article.

NEW VOICES is a Bread and Circus Magazine feature in which emerging writers share their views on aspects of contemporary culture.

__________________