Art Review: “Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist”

by Editors

THE ARTS

Review: “Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist”

Herman Trunk and the Modernist Still Life is on view at Endicott College, Beverly, MA from October 15-December 18, 2009. For opening times and directions see the Endicott webpage.

The catalogue, Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009), is available at Lulu.com.

By Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard

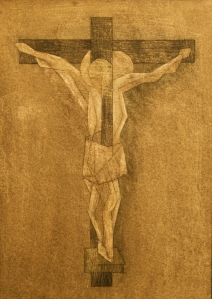

Crucifix (ca. 1930); Pencil with wax on paper; 10 x 14 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

With the advent of the modern world came an accompanying theory of secularization.[1] Enlightenment philosophers held that a developmental model of civilization demands that with modernization (read: rationalization) religion would necessarily decline.

Religion, of course, (in its broadest sense, including individual spirituality) has never left art or culture, and in a post-9/11 world I would suggest that even the most cynical critics would agree that life continues to be saturated with religious sentiment—spoken or unspoken.

In the visual arts, the period known as “Modernism” (the period from the turn of the last century until the 1960s) has been long associated with a firm commitment to individualism, iconoclasm and break with traditional institutions. This perspective became the mainstream means by which art critics and art historians came to measure successful art of the period.

In part, this perhaps explains why artists such as Herman Trunk, Jr. (1894-1963), a devout Roman Catholic who often imbued his paintings with overt symbolism, was exiled to the margins of American art history. This seemingly blind disregard for his work has recently impelled two Boston-area art historians, Cynthia Fowler and Dena Gilby, to reassess his religious and still-life works as masterful pieces in the Cubist and near-Surrealist styles. Fowler serendipitously discovered the artist in the process of researching her forthcoming book on hooked rugs designed by American modernists during the 20s and 30s.

The two scholars put together companion shows of Trunk’s work this Fall at their respective colleges: Fowler’s at Emmanuel in Boston (from 9/8-10/22) and Gilby’s at Endicott in Beverly (from 10/15-12/18). Fowler also organized and hosted a day-long symposium dedicated to the artist (“Religion and Modernism in American Art of the 1920s and 30s” on 10/3) and produced a handsome catalogue, Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009).

The catalogue contains essays by Fowler and Gilby, and also by Trunk’s nephew, Joseph (“Greg”) Smith. Smith grew up with the artist and his article sheds valuable light upon the man and anecdotes from his personal life, much of which was lived in Brooklyn, NY. Smith’s family photos and stories help to flesh out the biographical and iconographic picture painted by Fowler in her introductory and main essays. Fowler’s essays and show loosely cover Trunk’s figurative and landscape works, while Gilby’s are focused upon his still-lifes and flower pieces.

The artist that emerges from the well-illustrated catalogue is a complex and—at times—contradictory figure. Contradictory, perhaps, because of our own (aforementioned) inherited bias about what constitutes a Modern painter in the abstract style. We do not usually imagine, for example, a dedicated family man who sentimentally paints his wife’s Valentine’s chocolates, or the interlocking “Sacred Hearts” of Jesus and Mary in order to grieve the loss of his mother in visual terms.[2]

Sacred Hearts (1930); Watercolor and gouache on board; 20 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

It is Trunk’s return, perhaps, to tried-and-true symbols of traditional Christianity that sets him apart from his contemporaries such as Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe: artists with whom he was shown side by side at the Biennials of the Whitney Museum of American Art and Venice in his heyday.

Viewed in-person, the works are astounding for their rich color-sensibility and harmonies of geometry. Many are in either watercolor or gouache media, with only a couple in oil. According to Gilby,[3] during the Depression and war years the artist worked full-time in his family’s print shop, and often painted after-hours. Thus, this choice may have been due to monetary constraints, reasons of convenience, or both.

Luckies (1925); Oil on board; 10 x 8 in.; Collection of the family of Herman Trunk, Jr.

Indeed, the watercolors and gouache seem to be more adroitly handled than the oils, but the oil medium seems to have allowed the artist to work up thick impasto in order to gain sculptural effect and depth that challenge the two-dimensionality of the surface. The same insistence on delving into space is found in his beaverboard piece, “Artist’s Palette” (n.d.; Oil on board), where the artist incises geometric shapes into the surface, outlining his color passages and allowing the wood grain to show through. This treatment is reminiscent of Picasso and Braque’s experiments with Synthetic Cubism and work-a-day materials, and may have been learned during Trunk’s time at the Art Students League.

Interestingly, Gilby has also included a long vitrine in the Endicott show housing one of Trunk’s notebooks as well as some personal correspondence and family photographs. This archival material is an advantageous corollary to the still-lifes and landscapes. Further testament to continued strong family-ties among the Trunks, it was also brought to my attention that the frames for many of the works were hand-fashioned for the exhibitions by the artist’s nephew, including the attractive multi-layered bronze-colored frame surrounding “Black-Eyed Susan.”[4]

Far and away the greatest contribution made by the catalogue essays is that they frame Trunk’s work not according to his experimental style—as was done in a Hirschl and Adler Galleries retrospective in 1989[5]—but, rather through the lens of his Catholic faith. This faith is expressed in his use of traditional symbolism as well as his imagery redolent of nature as God’s creation.

The authors take great pains to explain how devout Trunk, his wife Irene, and indeed the whole Trunk family were. There are images of the local parish, stories about faithful trips to morning mass, and accumulated evidence of attention paid to traditional Biblical narrative, Catholic iconography as well as the imbuing of everyday objects with personal, devotional significance.

True, there are passages in the writing where one might wish for more in-depth analysis of the iconography of the works: for example, greater discussion of the floral and fruit symbols like roses and oranges most often associated with Mary, mother of Christ; or the use of jewel tones and thick outlines reminiscent of stained glass; or the use of metallic paint which calls to mind a long history of gilt panel altarpieces. However, the description of “Trees” (Cat. 6, c. 1930-35, watercolor and pencil on paper) as cathedral-like is enticing, as is the likening of the oft-mentioned tenets of mysticism in the vein of Kandinsky to those of “conventional faith.”[6] Overall the essays serve as an even-handed, valuable introduction to the artist and his unique milieu.

The catalogue and exhibition are highly recommended to those interested in Modern art, religious iconography, or a reconsideration of how the two might be considered more fruitfully in tandem.

________________

Addendum:

Since the original publication of this article, Dr. Gilby has brought to my attention that the title of the Endicott Show differs from the one I first listed here, the one published on the catalogue overleaf, in fact. I have fixed this above, correcting the title to read “Herman Trunk and the Modernist Still Life,” instead of “Modernist Specters in the Still Life Paintings of Herman Trunk, Jr.” as previously stated.

Furthermore, (in personal correspondence) Dr. Gilby takes slight issue with my assertions that her catalogue essay and the Endicott show “are specifically focused on Trunk’s Catholicism.” Though I may not have expressed with enough clarity Trunk’s many-layered connections to the worlds of Modern Art and the New York scene, I would maintain that the thread of Catholicism is readily interwoven into Gilby’s show and essay.

Agreeing whole-heartedly with Dr. Gilby, I would simply state that Trunk is a versatile, talented artist whose art is well-worth experiencing on any of a number of levels.

-Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, November 21, 2009

[1] Sally M. Promey, “The ‘Return’ of Religion in the Scholarship of American Art,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 85, no. 3 (Sept., 2003): 584.

[2] Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist (Emmanuel College, 2009), pp. 28-29.

[3] In a personal conversation on 11/6/2009.

[4] Again, personal conversation with Dena Gilby on 11/6/2009.

[5] See the exhibition catalogue, Herman Trunk (New York: Hirschl and Adler Galleries, 1989.)

[6] Herman Trunk, Jr.: Catholic Modernist, pp. 23, 25.

_____

Kimberlee A. Cloutier-Blazzard, Ph.D., is an editor of Bread and Circus Magazine and an Independent Scholar of Art History, specializing in Northern Renaissance and Baroque. Click here to send her email.

________________