Freedom Paintings

by Editors

NEW VOICES / JOURNEYS

Freedom Paintings

By Jessica Miles

While studying abroad this past June in Prague, Czech Republic, I traveled outside the city to gain a better understanding of the effects of Nazism on the country. I arrived in Terezín on a hazy Saturday afternoon and toured the Small Fortress of the Terezín Ghetto where thousands of prisoners were held against their will during the Holocaust.

“It mustn’t be forgotten,” she said.

This is why Mrs. Helga Weissová-Hošková visited that day; this is why she spoke. Mrs. Weissová-Hošková had come to share her story as a Holocaust survivor from Prague who was sent to the Terezín Ghetto on December 17, 1941. She was twelve when she arrived at Terezín.

“It mustn’t be forgotten,” she boldly stated.

She toddled into the room that day in a taupe pant suit and a clunky gold necklace holding a purse that was half her size on her forearm. She was no more than five feet tall with a slight arch in her back, salt and pepper hair, and crystal blue eyes. She gently placed her bag down on the chair and paused.

“I am here…to tell you…my story,” she said in broken English.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s nightmare began in Prague in 1941, when the Nazi regime expanded to the Eastern Block. She did not know her fate that day when her family was forced into a crowded truck and blindly relocated one hour away to Terezín, a small town in northwest Czechoslovakia. The Nazis had transformed Terezín into a labor camp where Czech Jews would work before being transferred to a concentration camp.

In December 1941, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her parents arrived at the Small Fortress of Terezín. Arbeit Macht Frei, read the message over the entranceway. Work Brings Freedom. The brick fortification surrounded by sprawling green hills was secluded and bare. Barbed wire lined the fortress walls, which were adorned with barred windows and doors.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s home was in the barracks of the Small Fortress isolated from the outside world. She was housed with several other Czech Jews. Yet, even in the dismal conditions, together they created normality however they could.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s home was in the barracks of the Small Fortress isolated from the outside world. She was housed with several other Czech Jews. Yet, even in the dismal conditions, together they created normality however they could.

“We kept our traditions. We were always together,” Mrs. Weissová-Hošková said as she recalled lighting the Chanukkah menorah in a dark loft within the fortress. She remembered gathering around the menorah with the other children, their eyes brighter than the burning flames.

However, the desolation overshadowed the mere moments of contentment. The smell of rotting bodies, the threat of typhoid, and the lasting despair lingered around every corner of the ghetto, but she never lost hope.

By night Mrs. Weissová-Hošková was crammed into the rickety wooden bunks overcrowded with emaciated figures yearning for sustenance as bugs crept across their frail bodies. By day she was one of thousands of Jews identified by the yellow Star of David on her sleeve, which she still carries with her.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková considered herself quite lucky, as she was never separated from her mother during the selection process. Her father was not so fortunate.

“We were told we were going to another ghetto. My father went ahead of us. I did not know I would not see him again,” she said. “We never found my father’s name on the lists [of prisoners registered at Auschwitz]. He was probably gassed before arriving at Auschwitz.”

Days later in October of 1944, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her mother were loaded into crowded trucks and once again blindly transferred from Terezín to Auschwitz. Sixteen days later, along with thousands of other Czech prisoners, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková and her mother were liberated by the Soviet army in 1945.

* * *

Aside from her words Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s story is also told through her artwork. With her paints and brushes, Mrs. Weissová-Hošková painted the truth behind the walls of the Small Fortress and was eager to share her work that day.

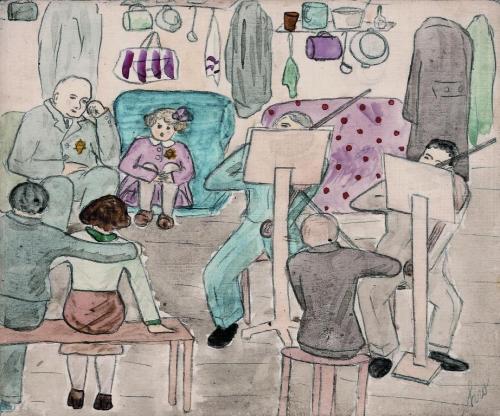

Violinists in the barracks. This painting of three prisoners providing entertainment in the barracks of the Small Fortress represents an escape from Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s surroundings. It is a symbol of unity; a man wraps his arm around a woman, while a young girl holds her knees to her chest as she listens to the violinists draw their bows along the strings of the violins.

_____

Terezín’s children. This painting symbolizes the children of Terezín who banded together and celebrated the traditions closest to their hearts. Lighting the Chanukkah menorah was one such tradition that took place within the walls of the barracks.

_____

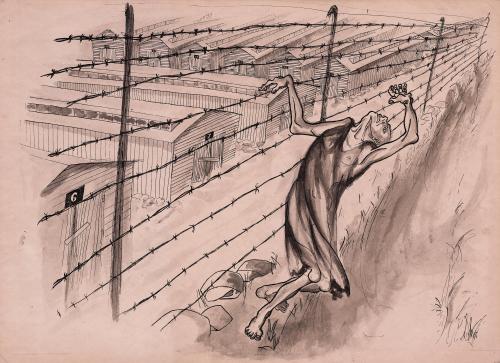

Vanished hope. A man falls against the jagged wall of barbed wire surrounding the Small Fortress. “This man had no more hope. He did not want to live anymore,” said Mrs. Weissová-Hošková. His gaunt figure falls to the ground, his hands still grasping the piercing barrier.

Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s drawings were later recovered following the termination of the Nazi regime and represent a cultural commemoration to the battle millions of prisoners fought for survival. Today, she is recognized internationally for her artwork and as an outspoken survivor of the Holocaust. Mrs. Weissová-Hošková’s pieces have been featured in several exhibitions, including A Child Artist in Terezín: Witness to the Holocaust. She has also been spotlighted in various publications for sharing her voice and her art with those who believe in her message, for those who believe it mustn’t be forgotten.

_________

Jessica Miles is a Bread and Circus Magazine contributing writer.

Text and photographs © 2009 Jessica Miles.

Paintings © 2009 Helga Weissová-Hošková. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of the Artist.

Thanks to Milan Polák of CIEE, Council on International Educational Exchange, for assistance in the preparation of this article.

NEW VOICES is a Bread and Circus Magazine feature in which emerging writers share their views on aspects of contemporary culture.

__________________